|

by Jenn Frank

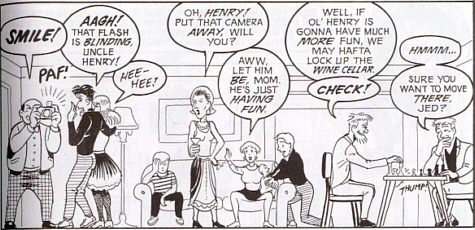

"…Comics are the synergy of pictures and words; great comics, though, are the synergy of art and literature. As editor Carl Potts says, 'the combining of graphics and the written word creates a product that is greater than pure written word or pure graphics could achieve.'"There's something that catches the eye when one sees a well-drawn, well-thought-out, modern comic strip, something that extends past the shallow, garish colors or the two-dimensional smiles of the superheroes of yesteryear. Many of today's comics - or as they often prefer to be called, "graphic novels" - seem to breed characters better suited to, say, a Russian novel. These characters are born out of the very nature of comic books, out of panels placed side-by-side, and out of frozen time. And the medium is built in such a way that the reader's perception of the comic book, in many ways, takes control of the story. As a result, the medium of comic books itself is conducive to the crafting of a divine or noble fool-type character, a Dostoevskyan idiot, by providing variability in a seemingly deterministic, linear narrative. Many modern comic book authors take full advantage of this universe, creating characters that are misunderstood, yet overpoweringly good. By examining modern comic book characters that seem to have all the traits of the archetypal divine fool, and comparing these characters to Dostoevsky's concept of the anti-hero, we emerge understanding the amazing and chaotic universe in which these comic book characters exist. -- The divine fool stands isolated from social convention, or perhaps even just a beat out of time. He is full of goodness, and he's probably ostracized for it. He endures incredible tragedy. He might even be compared to Christ. Today's writer/artists like Neil Gaiman, Jeff Smith, Adrian Tomine, Edward Gorey, Archer Prewitt, and Chris Ware have crafted substantial characters that virtually rise from the pages in three dimensions - and more than a few of these characters resemble the archetypal noble fool. The Archie comic book series, in addition to any number of spin-off characters' series, has been going strong since 1941, when Archie Andrews, "his pal Jughead, and a wistful blond named Betty made their debut in issue no. 22 of Pep" (Robbins 8). Archie, with his freckles, dork-hair, and wide black eyes, is naïve, impossibly good, and blissfully oblivious. As an exercise in aloofness, he is thus something of a social outcast. Archie, in spite of his wonderful intentions, perpetually botches whatever it is he's doing, miffs Betty or Veronica, or grates against the nerves of Riverdale High's principal, Mr. Weatherbee. Like Dostoevsky's model fool, Prince Myshkin, Archie Andrews feels the agony of being torn between two diametrically opposed women, and he cannot help but walk to the beat of a different drummer. In Neil Gaiman's "Calliope" from the Sandman series, Calliope is goodness personified, a being thousands of years old but with youthful naïveté. She is a muse of sorts, and is captured by a writer who enslaves her and forces her to infuse him with ideas for his books. The bewilderingly good character Fone Bone of the Bone series by Jeff Smith is a goofy, white, puffy cartoon, run out of Boneville because of something another one of his cousins did. So begins his adventures in the fantastic world outside of the one he knew. The premise for Bone, then, is entirely rooted in the ostracizing of a wise fool. And finally, in "Supermarket," from Adrian Tomine's series Optic Nerve, Mr. Lewis experiences the sort of social exclusion that can come only from a disability like blindness. Even today's superheroes have acquired certain Christ-like qualities. And comic books aren't always so subtle when alluding to the resemblance said superhero may bear to the Personification of Salvation and Redemption [fig. 1].

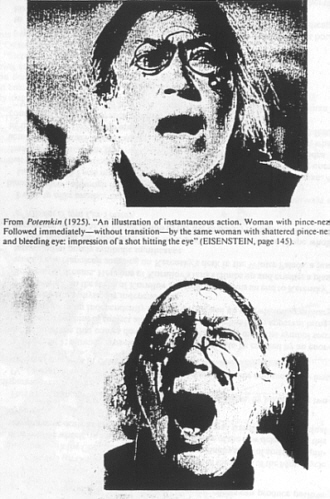

Fig. 1 The parallel that can be made between Batman and Christ is an obvious one. Batman, saviour to the masses of Gotham, confesses his own sense of mortality, with the silhouette of Christ in the background. From Arkham Asylum. -- But some of these characters merely resemble cosmic fools. True, constant, fatalistic torture really comes to few. Titular comic book characters like The Hapless Child, Jimmy Corrigan, and Sof' Boy seem to get the brunt end of the universe's sense of humor. They live in a perpetual state of social crucifixion and discontent. In the immortal words of Peanuts' Charlie Brown, "AAUGH!!" (Larkin 51). Many graphic novels' divine fools share the same genre of comic book, "alternative fiction." Alternative fiction stems from the underground movements of self-published comic books as well as "fanzines", often railing against the traditional, archetypal superhero that pervades comic book stores, as the caped Überman is intended for a very narrow demographic. In the early 1970s, when women's liberation was a very real and active movement, women infused the comic scene - dominated by testosterone-inspired pages, no less - with their own, independently published comics, attempting to take a stand and raise consciousness. "Despite the general male antipathy, 1970 saw an explosion of feminist underground newspapers all over America" (Robbins 85). These newspapers sprang up in academic settings and often featured comic strips by male and female authors alike. Other independent groups and individuals were doing the same thing. Underground publications eventually gave way to alternative fiction. Consequently, alternative fiction's characters, striving to be separate from the superheroes that fly around in long underwear, assume anti-heroic qualities. Edward Gorey, the renowned author/illustrator of countless illustrated books that boast a dark, woodcut style of realistic cartooning, died in April of 2000. He nonetheless remains a figurehead of sorts in the graphic novel industry, and is particularly idolized by numerous alternative fiction authors and illustrators. In Gorey's book The Hapless Child, a little girl named Charlotte Sophia learns that her father has died in the war. Horribly affected by this news, her mother falls ill and dies. Charlotte is placed in a boarding school, where she quickly becomes miserable. She escapes the school and faints in the street. She is eventually captured and sold as cheap labor, becomes blinded, and runs into the street. Her father, who "was not dead after all," has been driving through the city, searching for her, and in a twist of cruel irony, Charlotte Sophia runs in front of his car and is immediately killed. The Hapless Child peculiarly ends with the image of a winged demon dropping a framed portrait of Charlotte Sophia; if one searches through the panels of the story, one will additionally find that tiny horned figures and strange winged or tailed creatures peer out of nooks or from behind corners in almost every panel. In this manner, Gorey's story, while gruesomely humorous in its satire of Charlotte Sophia's heartache, takes on a disconcerting and even fatalistic tone. The recently published collection of Jimmy Corrigan's exploits is ironically subtitled The Smartest Kid on Earth (Ware). One must bear in mind that Jimmy Corrigan is neither smart nor a "kid." Jimmy is a 36-year old man; in his daily interactions with other characters, he is belittled and patronized. And, like many noble fools and antiheroes, Jimmy is haunted by a past he can't quite shake. Abandoned by his father as a child and now both harangued and infantilized by an attention-starved mother who neglected him in his youth, Jimmy epitomizes isolation and social crucifixion. The titular character of Sof' Boy (Prewitt) is a strange little puffball of a character, vaguely resembling the Staypuff Marshmallow Man from the comical 80s movie Ghostbusters. Sof' Boy - perhaps named for his unsinkable resilience - remains in good spirits, no matter what adversity comes his way. As a result, the comic strip is downright gruesome in its caricature of goodness. Sof' Boy is a modern village idiot. On a single morning, he announces, "Okay! Let's start the day!" He then mistakenly somersaults into the crosswalk of a street, is immediately run over by a car, and is urinated on by a passing dog. A rushed businessman mistakenly steps on Sof' Boy and, realizing Sof' Boy's presence, mutters, "Disgusting!" But Sof' Boy is unaffected. His flattened form pops back out with perhaps a puff of air, he shakes the urine off himself, and he says again even more brightly, "Okay! Let's start the day!" Instantly, he is struck by three more cars and a Mack truck. So begins issue one of Sof' Boy. -- The divine fool often seems to be fated, or ill fated, as it were, to meet some torturous end - a social crucifixion, if you will. But, like Prince Myshkin of Dostoevsky's The Idiot, the divine fool seems to stand outside the narrow path of social convention. He may indeed walk just a step out of time, in every possible sense of the expression. While his universe is seemingly governed by destiny, the divine fool's interaction with chance and variability is unlike anyone else's. The noble fool of comic book literature interacts with the medium of panels in a similar way. It would seem that the comic book, by nature, must conclude with a sealed fate. Panels, after all, are a linear, square-by-square narrative, and there can be no deterring from the established path, or can there? One of the most important tools in the transfer of information from author to reader is that of the reader's perception of things. In the reading of comic books, the audience plays an integral part in the storyline, possessing the capability to alter both the events and the ultimate meaning of a series of panels. This is accomplished through the process of montage. Montage is an important emotional device in poetry and film. It is the process of juxtaposing tangible imagery in order to craft a new, concrete metaphor. When the author or director uses a series of images, the audience's mind makes the jump, creating an almost involuntary connection. Elements ordinarily not associated with one another, when placed in some sort of sequence, thus produce a new abstract idea. Sergei Eisenstein refers to the montage as a sort of collision in the audience's mind (141). The images conflict with one another, and the audience resolves the dissonance by creating a connection, by providing closure. Eisenstein provides the example [fig. 2] of a film cut from a shot of a horrified woman wearing pince-nez to a shot of the same woman wearing shattered pince-nez. This time, her eyes are closed, and she appears to be in pain. The shots in sequence, he contends, give the audience the impression that she has been wounded by a gunshot to the face. The audience, in this case, involuntarily connects the two separate images.

Fig. 2 Examples of a film cut by Eisenstein. The two shots are in sequence, and the contrast between the two creates the montage. The audience experiences the illusion of a woman being shot in the face. From A Dialectic Approach to Film Form, pg 147 Montage allows important metaphors to be assigned in a short span of time, in a limited space, or in a certain number of syllables. Lyric poetry, film, and comic books are all different media that often have a designated amount of space in which the author, director, or illustrator must work. There must be an exclusion of information in order to make a metaphor fit into, say, lyric poetry. There is never a way to say everything. These media, then, seem constricting. But variability and chance occur when the audience or reader is expected to compensate for excluded information with his or her own imagination. Sometimes, creating metaphors in visual montage is even more effective than in lyric poetry and other textual montage. When a metaphor is presented as visual information, the audience is not told straight out, in words, what the metaphor is "supposed to be." Instead, the audience actively responds to the visual information with a metaphor. The mind makes the metaphor for itself. It is, in effect, a personal revelation. Printed visual montage is much different, of course, from animated visual montage, from performance, and from film. Film and animation actually use time to create metaphors. The conceptual "jump" on the mind's part is involuntary because time links the images. But comics are different. Clearly, on paper, time cannot exist because a single frame, an image standing alone, is likewise representative of a single instant, suspended indefinitely. "The basic difference [between animation and comics] is that animation is sequential in time but not spatially juxtaposed as comics are. Each successive frame of a movie is projected on exactly the same space - the screen - while each frame of comics must occupy a different space. Space does for comics what time does for film" (McCloud 7). With panels of images arranged spatially, with something like a comic strip, the mind must jump a physical gap (in both comics and in graphic design, this gap is called the "gutter"), linking one piece of story to the next.

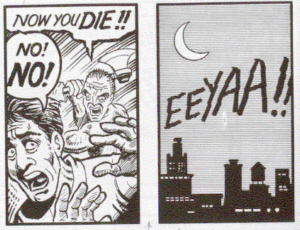

Fig. 3 Lewdness ensues: Triptych #77 by Thomas Florschuetz, effectively yet subtly uses spatial arrangement to create a montage that is all at once both disconcerting and sexual. From The Photography Book One of my favorite examples of a triggered response by using space instead of time is Thomas Florschuetz' photographic work, "Triptych #77." The photos on the right and left are of the bottoms of someone's feet, and the photo in the center is of a man's lips parted into an 'O' and of his slightly asymmetrical nose [fig. 3]. The pictures are "intended to be shown in gallery spaces, and to challenge audience responses" (Photography 151). The audience's gut response to this photo, obviously, is a lewd one: we perceive that the photo depicts spread legs, and we extrapolate that the man's open mouth has been translated into a sexual orifice. But, of course, these connections are merely suggested through spatial arrangement alone. Nothing lewd is ever said. The sexual metaphors are entirely a product of the mind. Thus, montage is largely made possible through the human tendency to manufacture closure. "[Comics are] a medium where the audience is a willing and conscious collaborator and closure is the agent of change, time, and motion," says comic book author and illustrator Scott McCloud (65). "Comics panels fracture both time and space…. But closure allows us to connect these moments and mentally construct a continuous, unified reality." McCloud provides the example of a single, violent comic panel depicting a villain and his victim. The next panel is merely the writing - no, the shadow - of a scream ("EEYAA!!"), stark against the night air [fig. 4].

Fig. 4 But how did he die? *Did* he die? (McCloud 66) But the man's death is never depicted. In fact, we don't know if he really did die. Perhaps he escaped. We don't know whose scream it was. In fact, we don't really know what happened; it is a choice left entirely up to the audience. "To kill a man between panels is to condemn him to a thousand deaths" (McCloud 69). In essence, everything is left up to the reader in comic books. Motion is absent, so the audience creates motion: "Here we have, temporally, what we see arising spatially on a graphic or painted plane. What comprises the dynamic effect of a painting? The eye follows the direction of an element in the painting. It retains a visual impression, which then collides with the impression derived from following the direction of a second element. The conflict of these directions forms the dynamic effect in apprehending the whole" (Eisenstein 141). But the audience, in using this method to create motion, also creates time [fig. 5].

Fig. 5 This is a single panel, but paradoxically, it isn't a single moment in time! As the moves from left to right in a single, sweeping motion, the illusion of time passing is in turn created (McCloud 95). A single panel, paradoxically, is hardly ever a single moment in time. Rather, the eye moves from left to right in a single, sweeping motion, creating the illusion of time's passage (McCloud 95).

Fig. 6 Similarly, this single space -- a woman's shape under the comfortable covers of her bed -- is separated into a visual staccatto, providing the illusion of both time and motion (Cho 102). The eye and mind can create time and motion at the same time - even though it is relating the two to a quasi-continuous plane of space [fig. 6]! It makes sense that the eye should perceive one panel, one long image, as several different moments in time. Time, after all, is a measure of a sequence of motions. Maimonides asserts that time is dependent on motion, and a lack of motion results in no sense of a temporal passage of time. But Maimonides concludes that motion is chaotic, a creative act (Seeskin 23 April 2001). If there is no motion in comics, then is there no chaos, no possible variability? Does Fate rule all? Certainly not: the audience negates a lack of motion - and thus, a lack of time - by creating both motion and time. Thus, the comic book is chaotic, it is a creative and variable process, and the audience supplies the chaos. One might argue that the chaos, movement, and time created as one reads a comic book are as two-dimensional and fabricated as the comic book panels themselves. But this is not so. William Blake contended that time itself is merely a construct of the human imagination (Garfield 14 May 2001). If this is true, the illusion of time in comic books is no more or less real than time itself. Admittedly, a designated pathway, a degree of fatalism, must always be present in comic books. One panel does lead to the next, with scarcely any deviation. But the means by which this action is achieved lies almost wholly in the mind of the audience. Consequently, there is an arguably infinite amount of variability in the comic book universe - variability that the audience itself is required to provide. -- Dostoevsky's The Idiot was written in a way that might be strikingly similar to the way comics are written. Fyodor Dostoevsky introduced "noise" into his novel - extraneous details and dangling threads of plot that result in what is known as informational "entropy." As more and more information is introduced, no matter how inconsequential the new information seems, it adds to the total amount of information presented. As information saturates the space, the work approaches a chaotic state of "maximum information" (Harris 1 May 2001). Thus, in his creation of dangling threads of plot, Dostoevsky created chaos, room for chance. He also wrote the book with no definite end in mind (Morson 5 February 2001). In like fashion, comic book authors often write their series as mere episodes, as multiple dangling plot lines, with no definite ends in sight. The comic book readers, in turn, provide the chaos and noise. Certainly, the noble fools seem fated in many ways: Charlotte Sophia is on a downward spiral from the start, Sof' Boy will always be proverbially defecated on by his urban environment, Jimmy Corrigan will always be dejected and rejected, and Charlie Brown will always miss the football when he goes for the kick. But the characters' respective comic books have this commonality with Dostoevsky's writing, and thus with much of Russian literature. Although they are perpetually ill fated, these "idiots" can meet their predictable dooms in any number of ways. The possibilities for failure, rejection, and social ostracizing are endless. -- Divine fools work so well in the comic book universe; here we have a medium that seems to be deterministic, and its characters seem to inevitably possess a set fate. But time works differently in comic books, just as divine fools seem so often to work differently with time. The Dostoevskyan idiot marches outside of everyone else's drumbeat, distant from the beaten track. His motions are different, his sense of time is different, and his fate often digresses from everyone else's. Therein lies the chance! The fool is ostracized because he is representative of the chaos in an otherwise comfortably static universe. He sees things differently. He is the noise, he is the variability, he is the example of what things would be like if people chose another course. He is, paradoxically, a personification of chance. Though it seems constricting to fit a certain amount of visual and textual information in a set frame, and to somehow maneuver hundreds of these small panels into some semblance of a story, comic book characters enjoy the potential for variability that a scant few other literary figures are gifted with. The comic book universe is, in fact, a chaotic realm: the individual takes hold of the story, and not every detail is "spelled out." Instead, the comic book author, in many ways, leaves the story dangling and open. He or she, as creator, leaves the interpretation of details up to the audience, to both chance and choice. Today's genre of alternative fiction effectively makes use of this potential, and Archer Prewitt, Chris Ware, and Edward Gorey all have used panel art to their advantage, creating sympathetic fools of whom Dostoevsky himself might be proud. --

Works Cited Other writings |